Cleanup on Aisle Thought

How bad ideas keep making it to checkout—and why we still pay the price.

I was reaching for orange juice when I noticed the Instacart shopper next to me. Phone in one hand, reusable bags in the other, he moved with the efficiency of someone who’d memorized every aisle. No browsing, no label reading, no checking if the oranges are actually ripe. Just execution—someone else's list, someone else's choices, someone else's groceries.

I thought about all those TikToks—women (and men!) ranting about male Instacart shoppers picking bruised bananas and wilted lettuce, grabbing the wrong milk, substituting in ways that make no sense.1 As someone who actually enjoys grocery shopping and knows the difference between Persian and English cucumbers, I’ve always found it funny. But watching him work, I got it. He's not shopping. He's completing a task.

As I continued my strut down the aisle, I realized this is how we shop for ideas now too. We’ve outsourced the browsing, delegated the discovery, and automated the selection. There are a lot of people living off someone else’s intellectual grocery list.

Last week, USC’s new interim president used the phrase “marketplace of ideas" in an interview with USC Today. He meant it earnestly, referencing academic discourse and diverse perspectives. But it got me thinking about how long that metaphor has been around. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes coined it in 1919, back when people actually walked through markets. The phrase suggested the best ideas would rise to the top through open, democratic competition.

Now? We let algorithms do the shopping, influencers do the picking, and we accept whatever substitutions show up at our door. Often without checking the expiration date.

Paper or Plastic Thoughts

The original marketplace Holmes imagined was supposed to work like an actual market—messy, competitive, and alive. “The best test of truth,” he wrote, “is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market.” Bad ideas would spoil in the sun while good ones found buyers.

Holmes had reread Mill’s 'On Liberty' months before writing Abrams v. United States, absorbing its argument that even false opinions serve a purpose. As foils, as partial truths, as reminders of why we believe what we believe. The market wouldn’t promise truth, but it offered the fairest trial we had.

Back then, shopping for ideas meant real browsing. You’d walk through newspapers, bookstores, university halls. You’d examine arguments like produce: Is this fresh? Is it worth the price? Will it last the week?

There are a lot of people living off someone else’s intellectual grocery list.

The produce section held the breaking ideas, the just-published studies, the hot takes everyone was talking about this week. You knew they’d spoil fast. That viral opinion piece would be forgotten by Thursday. That breakthrough study would be contradicted next month. But that was fine. Freshness had its own value.

The center aisles held the long-shelf-life ideas. “Money can’t buy happiness.” “Technology is making us disconnected.” Takes that had been processed, preserved, and resealed for every generation. Labels updated, contents unchanged, all nuance boiled out.

And yes, every store had a clearance rack. Ideas past their expiration date, marked down but never removed. Debunked theories. Outdated stereotypes. The intellectual equivalent of dented cans and torn packaging. You could see the damage, but somehow they still moved inventory.

Here’s where the metaphor starts to unravel. It implies all ideas deserve shelf space. That every opinion merits equal consideration. But Holmes knew better. He opened his Abrams dissent by admitting that “persecution for the expression of opinions seems to me perfectly logical.” Some ideas actually are poisonous. The market doesn’t sort truth from lies; it sorts what sells from what doesn’t. And clearance-rack ideas move precisely because they’re cheap and familiar—not because they’ve survived any test.

The point was, you walked the aisles yourself. You chose what went in your cart.

Instacart for Ideas

The shift happened gradually. First, we started shopping at just one store—our preferred news source, our social media feed, our political bubble. Then we stopped shopping altogether. We subscribed. We followed. We let the algorithm learn our preferences and deliver our daily dose of discourse.

Here’s the thing about modern choice: it’s simulated. We think we’re browsing, but we’re really just selecting from pre-curated options. Like a salad bar where invisible hands stock the bins, we pick from what’s already been picked for us. The algorithm isn’t showing you the whole store. It’s showing you end cap displays designed to move products.

The old news principle “if it bleeds, it leads” has evolved into something more insidious: if it enrages, it engages. The algorithm is like that Instacart shopper who grabs bruised bananas and doesn’t care. You still get billed, and they still get paid. Except instead of bruised fruit, you’re getting damaged discourse. Conspiracy theories with better conversion rates than careful analysis. Hot takes that spoil on contact, but keep you coming back for more.

When your Instacart shopper can’t find what you ordered, they make their best guess. But when algorithms can’t find the balanced take you need, they substitute whatever keeps you scrolling. You wanted journalism; they delivered clickbait. You ordered nuance; here’s polarization. Close enough, right?

We’ve become intellectual shut-ins, living off whatever gets delivered. It’s not nourishing you. It’s feeding the machine. The algorithm doesn’t do discovery. It does more of the same…and faster.

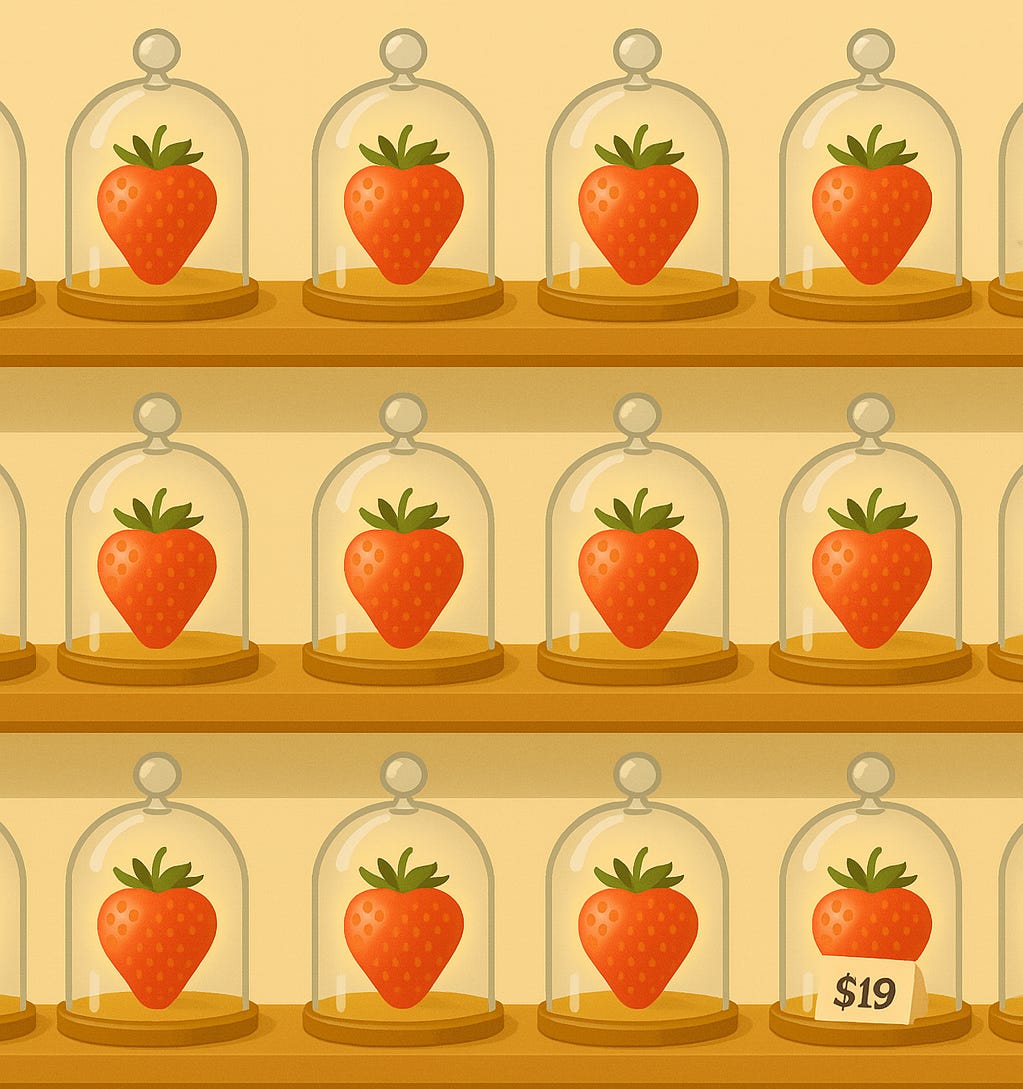

The $19 Strawberry Theory

In Los Angeles, people were paying $19 for a single viral strawberry.

Sixteen million people watched someone eat fruit that costs more than the federal minimum wage. The comments were predictably outraged: “dystopian,” “late-stage capitalism,” “Hunger Games vibes.” But it sold out immediately.

Erewhon, the upscale market selling it, feels less like a grocery store and more a performance venue. Shopping becomes content. People flew to LA just to walk the aisles and film the experience. It's pilgrimage as lifestyle branding.

This is “accessible luxury”—expensive enough to feel exclusive, cheap enough that middle-class consumers can participate once for Instagram. The same psychology drives the luxury idea market. Russell Brunson’s funnel empire works on identical principles: start with a $100 challenge, graduate to a $997 course, eventually hit that $10,000 inner circle. Intellectual consumption as a status ladder.

Hailey Bieber’s smoothie costs $20 and generated $760,000 monthly across just ten locations. The ingredients—hyaluronic acid, sea moss, collagen peptides—transform a drink into a lifestyle statement. The intellectual equivalent would be thought leaders selling “exclusive insights” behind paywalls, turning common sense into premium content. You’re buying membership, not information.

But what I find interesting is how criticism becomes marketing. Every TikTok mocking Erewhon’s prices is free advertising. Every takedown of overpriced courses spreads their reach. We’ve created an economy where performing consumption matters more than consuming.

We start believing that valuable ideas must be expensive, that common knowledge can’t be wisdom, that if everyone can afford it, it must not be worth having. The democratization of luxury thinking means everyone can play at being elite—for the right price.

What’s in Your Cart?

The hardest part about all this is that I’m not some neutral observer standing outside the system, coolly analyzing everyone else’s poor shopping choices. Holmes called his own beliefs his “can’t helps”—things he couldn’t help believing, even while knowing they might be wrong. We all have our can't helps filling our carts. The question isn’t whether you’re above the marketplace’s manipulations. None of us are. The question is whether you notice what you’re buying and why.

The marketplace isn’t gone. But we do have to leave the house.

Looking at my own intellectual habits, I’ve bought the flashy hot takes at checkout. I’ve subscribed to the premium newsletters that repackage free information. I’ve let the algorithm serve me the same comfortable ideas week after week, like ordering the same takeout every Friday.

But here’s what I try to keep in my cart:

One idea I keep rediscovering: Genuine curiosity beats performed sophistication every time. The best conversations I’ve had started with “I don’t understand this—can you explain?”

One I had to throw out: That more information automatically means better decisions. Sometimes it’s better to walk one aisle slowly than sprint the whole store.

One I wish more people would try: Shopping in the international section. Not metaphorically—actually reading news from other countries, essays in translation, perspectives from places where the “marketplace of ideas” looks completely different.

The marketplace isn’t gone. But we do have to leave the house. We have to walk the aisles ourselves. Sift through the noise. Check the expiration dates. Be willing to put things back on the shelf. Because when we stop browsing, we stop discovering who we might become.

Holmes believed the best test of truth was whether an idea could survive in open competition. But maybe today, the test isn’t if an idea can win. It’s if we’re still willing to shop for ourselves. If we can tell the difference between what’s fresh and what’s just packaged well. If we remember that the best ideas, like the best produce, are still worth choosing with care.

The algorithm will keep delivering. The luxury performances will keep trending. But somewhere between the Instacart efficiency and the Erewhon excess, there’s still a market worth walking through.

Even if it means occasionally ending up with bruised bananas. ⁂

🛒 Now available for paid subscribers:

What’s In My Cart is the companion to Cleanup on Aisle Thought—a curated, aisle-by-aisle guide to the essays, habits, tools, and ideas I’m carrying, questioning, or slowly defrosting. From Beyoncé to boundary-setting, it’s a deeper dive into what’s been nourishing (and nudging) me lately.

🛒 What's In My Cart

I mentioned at the end of Cleanup on Aisle Thought that I try to keep certain things in my intellectual cart. This is what I’ve picked up in the marketplace of ideas. Cart’s full.

💌 Love INHERITANCE? Help it grow. Refer friends and earn free months for spreading the word.

Like this one: “POV: You have another straight male Instashopper.”

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser