Nobody’s Enjoying This

Only 9% of Americans say they enjoy following the news. I used to be one of them.

I used to love watching the news. Not in an eat-your-vegetables way. I genuinely looked forward to it. I would come home and turn on MSNBC or CNN and watch the pundit roundtables the way other people watch sports. Who had the better argument. Who got caught off guard. Who said something so sharp the whole panel went silent. It was entertainment and education at the same time, and I never once thought of it as a chore.

Then I became a journalist, and following the news became work. I kept up because the job required it. I monitored feeds and breaking alerts and competitor coverage because falling behind meant falling behind. The pleasure didn’t disappear overnight. It just got buried under the professional obligation to always be current.

Then I left the newsroom. And without the requirement to stay plugged in, I started to notice how much of my news consumption had become automatic. I wasn’t choosing to be informed. I was just still doing it out of habit and some inherited sense that a person with my background should always know what’s going on.

I also deleted my social media accounts over a few years. X (formerly Twitter) went first, right around the time Elon Musk bought the platform and removed verified blue checkmarks from journalists and other trusted sources of information. When it disappeared, I remember thinking this platform just told everyone it no longer values the distinction between verified information and everything else. I didn’t need to stick around to see where that was heading. Instagram went next. Then TikTok. And finally LinkedIn, earlier this year.

And if I’m being honest, I don’t always know whether I’m as informed as I should be. That part nags at me.

Pew Research Center released a report this week called “Americans’ Complicated Relationship With News.” They surveyed more than 3,500 adults and ran nine focus groups. The findings describe something I recognized immediately.

Only 9% of Americans say they follow the news because they enjoy it.

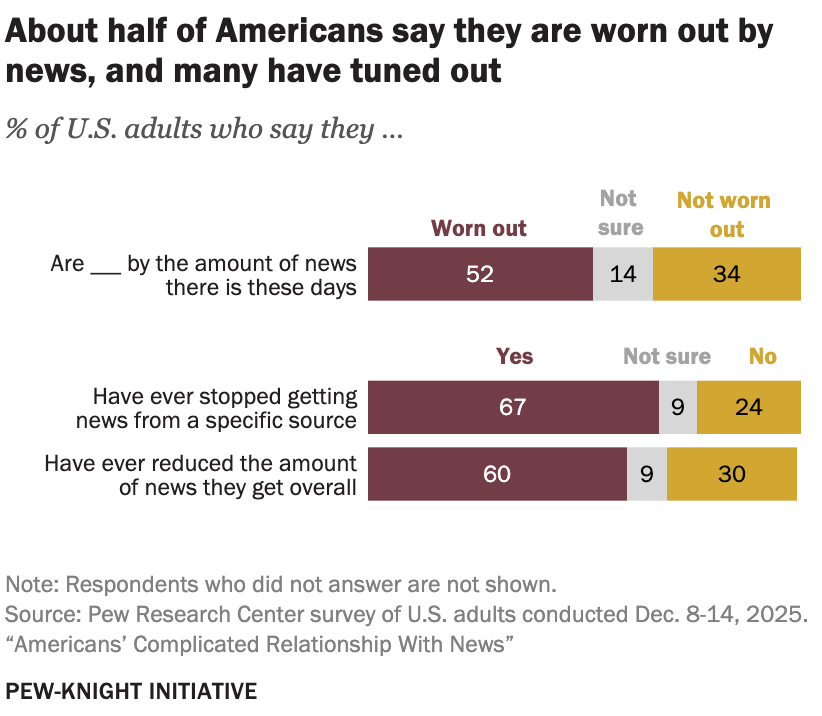

Nearly a quarter say they do it only because they feel like they should. About half say it’s some mix of both. And 16% say they don’t follow the news at all. The country that invented the 24-hour news cycle has mostly stopped enjoying what it produces. Six in 10 have reduced how much news they consume overall. Two-thirds have dropped a specific source entirely. And yet, eight in 10 Americans still say people have a civic responsibility to be informed when they vote. They believe in the idea of an informed public. They’re just exhausted by the experience of trying to be one.

I know that exhaustion. I was reacting more than reading. My attention was thinning and I could feel it happening, but kept going because I thought that was what informed people did.

The report found that Americans are now split evenly between those who seek out news on purpose and those who just happen to come across it. Among adults under 30, nearly three-quarters say news finds them rather than the other way around. Among adults 65 and older, nearly three-quarters say the opposite.

I turn 44 this summer. I remember both versions. Choosing to turn on the television at a specific hour. Choosing to buy a newspaper. And then the gradual shift into news arriving without invitation, in every feed, on every app, and in push notifications I never signed up for.

More than half of adults under 50 say they’re worn out by news. About half say most of what they encounter doesn’t feel relevant to their lives. That tracks with what I saw when I spent a year in graduate school researching algorithmic bias on TikTok. Black LGBTQ+ creators told me they were being suppressed by the platform’s own systems, forced to avoid certain keywords and time their posts strategically just to reach their audiences. The information environment was never neutral. What reaches you has always been shaped by systems most people never see.

The report also measured how much Americans trust themselves versus each other when it comes to sorting out what’s accurate. Almost eight in 10 say they’re confident in their own ability to check whether a news story is true. But only about a quarter feel that way about other people. Everyone believes they can figure it out. Almost nobody believes anyone else can.

When Americans describe what “doing your own research” means, the most common answer is comparing information from different sources. But about seven in 10 also say it means questioning what major news organizations report. A similar share says it means questioning official or governmental sources. The phrase has become something people say when what they really mean is: I don’t trust the institutions that are supposed to tell me what’s happening.

I spent years producing news for an audience that increasingly felt that way. I watched the distrust grow. And at some point I realized I was developing my own version of it. Not the conspiratorial kind, but the kind where you’ve seen enough of how the machine works to know that what gets published is shaped by what gets clicked, what gets funded, and what fits the editorial window that day.

There’s a section of the Pew report about paying for news that I think about as someone who now publishes a paid newsletter. Only 8% of Americans believe people have a responsibility to pay for news. Only 16% have actually paid for any news source in the past year. When asked how news organizations should make their money, the most common answer was advertising.

One focus group participant said he can’t afford to subscribe to every writer he likes. Five dollars here, five dollars there. It adds up. He’s right.

I spent years inside newsrooms funded by advertising, and I know what that model does to editorial decisions. The stories that get traffic aren’t always the stories that matter. Paid subscriptions are imperfect. But they mean the reader is there on purpose.

I now subscribe to a handful of writers and publications I’ve chosen on purpose. Nothing arrives by algorithm. The volume is lower, and what comes through actually matters to me.

But I’d be lying if I said I’ve figured it all out. Some mornings I wonder if I’ve pulled back too far and if there’s something happening that I should know about and don’t. I wonder if the distance I’ve created between myself and the news is freedom or just avoidance dressed up as intention.

The Pew report’s most striking finding is the simplest one. When researchers asked Americans why they follow the news, the most honest answer from most people was: because I feel like I should.

I followed the news for that reason for a long time. I followed it because I loved it, and then because my job required it, and then because I thought I was supposed to. Somewhere along the way, the love part disappeared and I kept going on obligation alone.

I stopped. I’m still figuring out what comes after that. I suspect a lot of people are. ⁂